5K Qs

Gold Member

- Joined

- Jul 20, 2014

- Messages

- 15,143

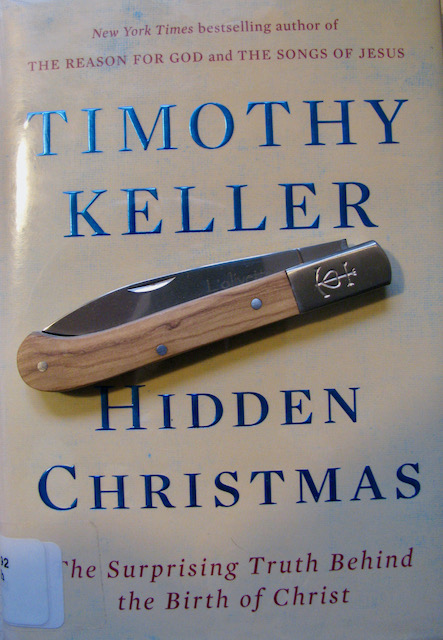

I read this book earlier this month, and thought I ought to post it now since it's Christmas-themed. As is usually the case when I've read books written by Keller, I enjoyed interesting discussions and encountered thought-provoking ideas about what the Bible says (in this case about Jesus' birth). Here are the chapter titles from this 160-page (relatively small pages) book:

2. The Mothers of Jesus

3. The Fathers of Jesus

4. Where is the King?

5. Mary’s Faith

6. The Shepherds’ Faith

7. A Sword in the Soul

8. The Doctrine of Christmas

Chapters 2 and 3 pointed out fascinating things about the genealogies of Jesus in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke; Chapter 4 discussed the Wise Men and Herod; Chapters 5 and 6 presented thoughtful discussions of the nature of the faith of Mary and of the shepherds; and Chapter 7 addressed the harsh comments of old man Simeon in the temple rejoicing that he was able to witness the coming of God's Anointed One.

- GT

Table of Contents:

1. A Light Has Dawned2. The Mothers of Jesus

3. The Fathers of Jesus

4. Where is the King?

5. Mary’s Faith

6. The Shepherds’ Faith

7. A Sword in the Soul

8. The Doctrine of Christmas

Chapters 2 and 3 pointed out fascinating things about the genealogies of Jesus in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke; Chapter 4 discussed the Wise Men and Herod; Chapters 5 and 6 presented thoughtful discussions of the nature of the faith of Mary and of the shepherds; and Chapter 7 addressed the harsh comments of old man Simeon in the temple rejoicing that he was able to witness the coming of God's Anointed One.

- GT

Last edited: